The 2012 revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference classified vasculitis on the basis of the size of predominantly affected vessels, as large-, medium- or small-vessel vasculitis.1 Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) associated vasculitis is a systemic autoimmune disease that primarily involves necrotizing inflammation of small- and medium-sized vessels. However, ANCA-associated vasculitis can occasionally extend to large vessels, including the aorta, supra-aortic trunks and pulmonary arteries, challenging its classical categorization.2,3 The main subtypes of ANCA-associated vasculitis are granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA), microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) and eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA).

Pulmonary artery stenosis, although rare, is an important clinical entity that can be either congenital or acquired. Acquired causes include vasculitis, pulmonary thromboembolism and extrinsic compression by mediastinal masses or lymphadenopathy.4,5 Large-vessel vasculitides, such as Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis and Behçet’s disease, are well established causes of pulmonary artery involvement. In contrast, large-vessel involvement in ANCA-associated vasculitis, including pulmonary artery stenosis, is far less common and often under-recognized.5

Here, we report a rare case of bilateral pulmonary artery stenosis secondary to GPA, underscoring the importance of recognizing large-vessel involvement as a potential manifestation of ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Case Presentation

A 62-year-old woman with a history of well-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented with a progressive constellation of symptoms that began in early 2021. A nurse herself, initially she reported “hearing a bruit” in her chest without associated symptoms.

Around this time, she developed recurrent nasal congestion with bloody discharge and sinus infections. Over the ensuing months, she experienced progressive left-side hearing loss, recurrent otitis media requiring tympanoplasty and arthralgias. A few months later, she noted progressive bilateral leg swelling. Her physical therapist identified worsening exertional dyspnea and auscultated a heart murmur. She also experienced worsening fatigue and noted scattered petechiae on her legs, arms, and abdomen.

Given her worsening dyspnea, leg swelling and palpitations, she was referred to a cardiologist. A transthoracic echocardiogram revealed severe pulmonary hypertension with an estimated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) of 102 mmHg, right ventricular dilation and a normal ejection fraction.

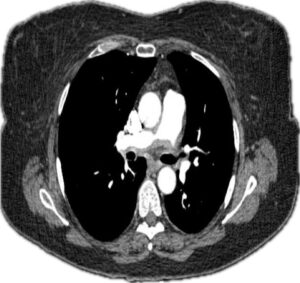

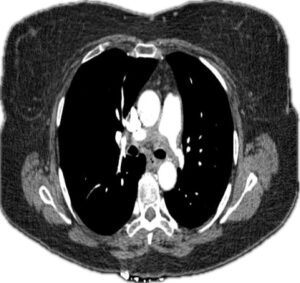

Holter monitoring ruled out arrhythmias. A computed tomography and angiogram (CTA) of the chest revealed ill-defined, soft-tissue thickening surrounding the right and left main pulmonary arteries, with moderate stenosis (see Figures 1 and 2).